The sirens were the first thing people noticed.

Then came the sharp, metallic voice over the loudspeakers, cutting through the ordinary hum of a weekday morning in downtown Sacramento. Inside the government building, coffee cups were left half-full on desks, screens unlocked, documents abandoned mid-sentence. At first, a few people looked up, expecting a drill. Then they saw the faces around them-pale, confused, phones already in hand. Within minutes, stairwells filled, the air thick with rushed footsteps and whispered questions no one could answer.

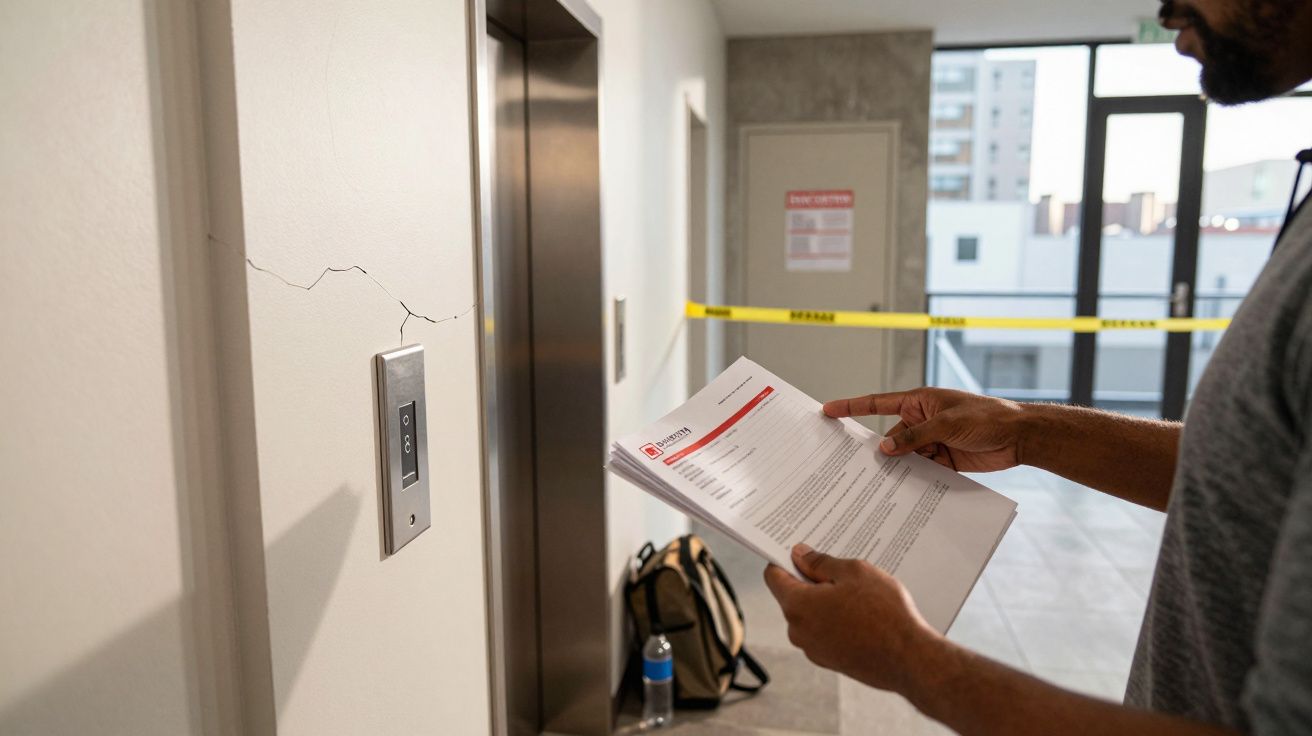

Outside, the California sun kept shining, almost indecently bright, as staff gathered behind yellow tape. Some tried to joke about it. Some didn’t say a word. The word “threat” drifted through fragments of conversation, but no one knew what kind. No smoke. No visible danger. Just that low, slow dread that something might be terribly wrong.

And the strange part is what people remembered most afterward.

Fear in the corridors of power

The building that emptied in minutes isn’t just any Sacramento office block. It’s one of those anonymous-looking government buildings that quietly holds the machinery of public life: payroll teams, policy analysts, clerks who know every comma in every regulation. On this day, all of that suddenly froze. Files stayed open. Meetings stopped mid-sentence. A security alert went out, and within seconds the normal hierarchy of power didn’t matter much anymore.

What people felt, more than anything, was how quickly the familiar can tip into the surreal. One moment, someone’s arguing about a budget line. The next, they’re in the parking lot holding a plastic visitor badge, staring at a building they’ve walked into a thousand times and wondering if it’s safe to go back.

For one employee, the break happened mid-email. She hit “send,” heard the alarm, and never saw the reply.

According to several staff members who later spoke quietly in nearby coffee shops, the first sign that this wasn’t a routine test was the tone of the security guards. These are people who have seen it all: protests, fire alarms, suspicious packages that turned out to be forgotten lunches. This time, their eyes were scanning every angle. Their gestures were sharper. “Move away from the entrance, please,” came not as a suggestion, but as an order with something heavier between the words.

One worker, still clutching a folder as if it were a shield, described how the crowd reacted when someone muttered “bomb threat.” No confirmation. No official statement, at least not yet. Just that phrase hanging in the air, passing from group to group. People hate an information vacuum, so they start filling it themselves-with headlines they’ve read, memories they wish they didn’t have, and worst-case scenarios running at high speed behind their eyes.

Statistics on government building evacuations rarely make the front page unless there’s a dramatic twist. Yet incidents like this, triggered by security alerts or suspicious items, have been quietly rising in large cities. Sacramento, seat of California’s political power, isn’t immune. Every new scare leaves an invisible residue on the people who work there, even if the threat turns out to be nothing.

Behind the scenes, the logic of what happened is almost clinical. Security protocols are designed to react fast, with very little room for hesitation. A suspicious object, a credible threat called in, a sensor triggered-and suddenly the decision tree narrows sharply. Evacuate first, explain later. In a downtown packed with offices and state buildings, one wrong call could affect thousands of people. So the system leans toward caution, even if that means disrupting hundreds of lives for something that ends up being harmless.

From the outside, it can look chaotic: people streaming out, streets blocked, a swarm of flashing lights. Inside the chain of command, it’s more like a script rehearsed in memos and training sessions. Buildings have zones, exits, roles assigned in advance. The staff might not remember every step, yet their bodies follow the flow. That’s the paradox of modern security: the more invisible it is when things go right, the more shocking it feels when it suddenly takes center stage.

Once the all-clear eventually arrives, the logic of the day splits in two. Officially, the system worked. Unofficially, some hearts keep racing long after the sirens stop.

How people cope when normal disappears in 30 seconds

What happens in those first few seconds after a security alert tells you a lot about how people really handle fear. Some grab their bags and laptops, as if their work might protect them. Others leave everything behind and just move. A few stand frozen, waiting for someone to tell them exactly what to do. In this Sacramento building, the small gestures mattered: a manager holding a stairwell door for her team, a stranger steadying an older gentleman on the last steps, someone passing around a bottle of water outside like it was a lifeline.

One quiet method that emerged later in conversations: people mentally mapped their exits. From desk to hallway. From hallway to stairs. From stairs to the street. Tiny, practical thoughts cutting through the static of fear. In the middle of a security scare, this kind of simple, almost boring focus can mean everything.

On a sidewalk near the scene, two colleagues exchanged a look and a sentence that could have been said in any city after any alert: “At least we’re all out.”

One story spread among staff in the days that followed. A woman in her 20s, fairly new to the job, had been in the restroom when the alert sounded. No bag, no phone, no keycard in hand. She walked out into a corridor already half-empty and had to follow the sound of movement rather than the official signs. Later she admitted to a coworker that she’d never really noticed the evacuation map on the wall near her desk. Why would she? It was just background ink, like the notices about printer maintenance or the flyer for the charity bake sale.

On a normal day, those details barely register. During a crisis, they suddenly matter. Yet the truth is, most people don’t memorize routes or rehearse what they’d do if something went wrong. Let’s be honest: nobody really does that every day. When the real alert comes, they’re improvising in real time, guided by crowds, instinct, and the hope that whoever designed the building knew what they were doing.

For the security teams, this isn’t abstract. They count seconds. They notice where people bunch up in bottlenecks. They later replay footage or reports, asking themselves uncomfortable questions: Did people get the message clearly enough? Did anyone stay behind? Where did panic start creeping in? The answers shape the next drill, the next memo, the next small change no one notices until the sirens sound again.

One of the unglamorous but concrete ways staff can protect themselves in moments like this is almost embarrassingly simple: take ten seconds, once in a while, to really look around. Where’s the nearest exit that isn’t the one you came in by? Is there a stairwell door at the other end of the hallway? If you had to leave this building without your phone, without your bag, without your normal routine, which direction would your feet automatically turn?

A practical habit some Sacramento employees say they’re adopting now is to run a quiet “what if” check when they enter a new meeting room or floor. Not in a paranoid way, not scanning every face-just a quick mental note: door there, stairs there, window here. One even mentioned making a tiny sketch in the corner of her notebook during long meetings, more as a way to feel anchored than from any real expectation of danger. It’s the kind of invisible prep that doesn’t make you heroic, just slightly more ready than before.

The other key gesture is emotional rather than physical: checking in with colleagues once the alert is over. Some will shrug it off on the surface and then replay the whole thing at 3 a.m. A simple “How are you holding up after that scare?” can act like a pressure valve. Nobody wants to be the person who admits they were terrified while everyone else jokes about the wasted morning. That’s why normalizing the conversation afterward matters almost as much as knowing where the exits are.

“I kept thinking I was fine,” one worker confessed later, “until my hands started shaking when I tried to type an email in the afternoon. That’s when I realized the fear had just gone underground for a few hours.”

For some, the Sacramento evacuation has turned into a shared reference point. The “Do you remember where you were when the alert came?” question pops up over lunch. Inside those stories, a few recurring themes keep returning:

- Who stayed calm and quietly helped others down the stairs.

- Who froze, and then moved only when someone else nudged them.

- Who went home early afterward because their body was still buzzing with adrenaline.

- Who acted like nothing happened and buried themselves in spreadsheets.

- Who decided to finally read the emergency email they’d ignored three times.

What lingers after the sirens stop

When the all-clear finally comes, it rarely arrives with the same drama as the alarm. There’s no big cinematic moment, just a gradual shift. Radio chatter eases. The crowd starts to thin. People edge back toward the building, half-expecting to be turned away again. Inside, the fluorescent lights are as unforgiving as ever, casting the same blue-white glow on the same desks. But something in the air has shifted. The place that once felt solid now carries a faint question mark.

Some workers simply sit back down and pick up where they left off, as if the day had just been briefly paused. Others can’t help scanning for exits a little more often, listening with new ears to every loud noise in the hallway. One person described it like this: “It’s like when you trip on a staircase you’ve used a hundred times. You keep walking, but a part of you doesn’t quite trust that step anymore.” That tiny fracture in trust doesn’t scream. It just hums quietly in the background.

Moments like this in Sacramento-and in countless other cities-raise uncomfortable, necessary questions. How safe do we really feel in the places where we’re supposed to be “just working”? What does it do to a community when the buildings of power start to feel fragile, even for an hour? The official line will talk about preparedness, coordination, response times. Between colleagues, the conversation is rawer: “What if it had been real?” “Would I have known what to do?” “Who would I have tried to call first?” Those unspoken calculations don’t disappear easily.

And maybe that’s where this story quietly lands: in the space between routine and risk. The Sacramento scare will probably be filed away in some internal report as an incident managed, protocols followed, operations resumed. For the people who stood barefoot on the pavement holding their office shoes, or who watched bomb-sniffing dogs circle the building they once entered without a thought, it sits differently. A reminder that normal can evaporate in 30 seconds. A nudge to look up once in a while and really see the exits. A story they might one day tell someone who wasn’t there-not to frighten them, but to say: “This is what it felt like, from the inside.”

| Key point | Detail | Why it matters to the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Human reaction to an alert | Confusion, rumors, sometimes conflicting instincts | Recognize yourself in the reactions described and feel less alone |

| Logic of security protocols | Fast decisions, evacuate before explaining, chain of command | Understand what happens behind the scenes during an alert |

| Concrete actions to take | Identify exits, talk after the incident, small low-key habits | Remember simple actions that can reduce panic |

FAQ

- Was there an actual explosion or attack in the Sacramento building? At the time of writing, authorities described it as a security alert that prompted an evacuation, with no confirmed attack or explosion reported.

- Why do buildings get fully evacuated even when the threat is unclear? Security protocols are designed to prioritize lives over convenience, so when a threat reaches a certain threshold, evacuation becomes the default option.

- How long do these kinds of evacuations usually last? It varies widely, from under an hour to several, depending on how long it takes bomb squads and security teams to inspect and clear the area.

- What should I personally do if I’m ever in a similar situation? Follow instructions from security staff, move calmly toward the nearest exit, avoid using elevators, and stay alert without spreading rumors.

- Do these incidents really change anything for staff afterward? Often yes: people become more aware of exits, take drills more seriously, and talk differently about safety and vulnerability at work.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a Comment