On a weekday morning at Tokyo Station, the restroom looks like a control room disguised as a sanctuary.

Japan’s toilets have long been famous for warm seats and whisper-quiet bidets. The surprise twist is what’s happening to the paper: it’s moving beyond the body, reshaping habits, and quietly redrawing the rules of hygiene in public and at home.

A small dispenser sits beside the usual roll with a tiny pictogram of a smartphone, and a commuter in a navy suit pulls a square, wipes his screen, and slips the phone back in his pocket, completely unfazed. Two stalls down, a cleaner folds the end of a roll into a neat triangle, like a tiny signal flag saying, “We’re ready.”

People exit, shoulders looser, screens cleaner, and somehow the whole place feels less tense. You can almost hear the hum of a giant city keeping its cool in the quietest corner it has. This changes the script.

The day toilet paper left the body

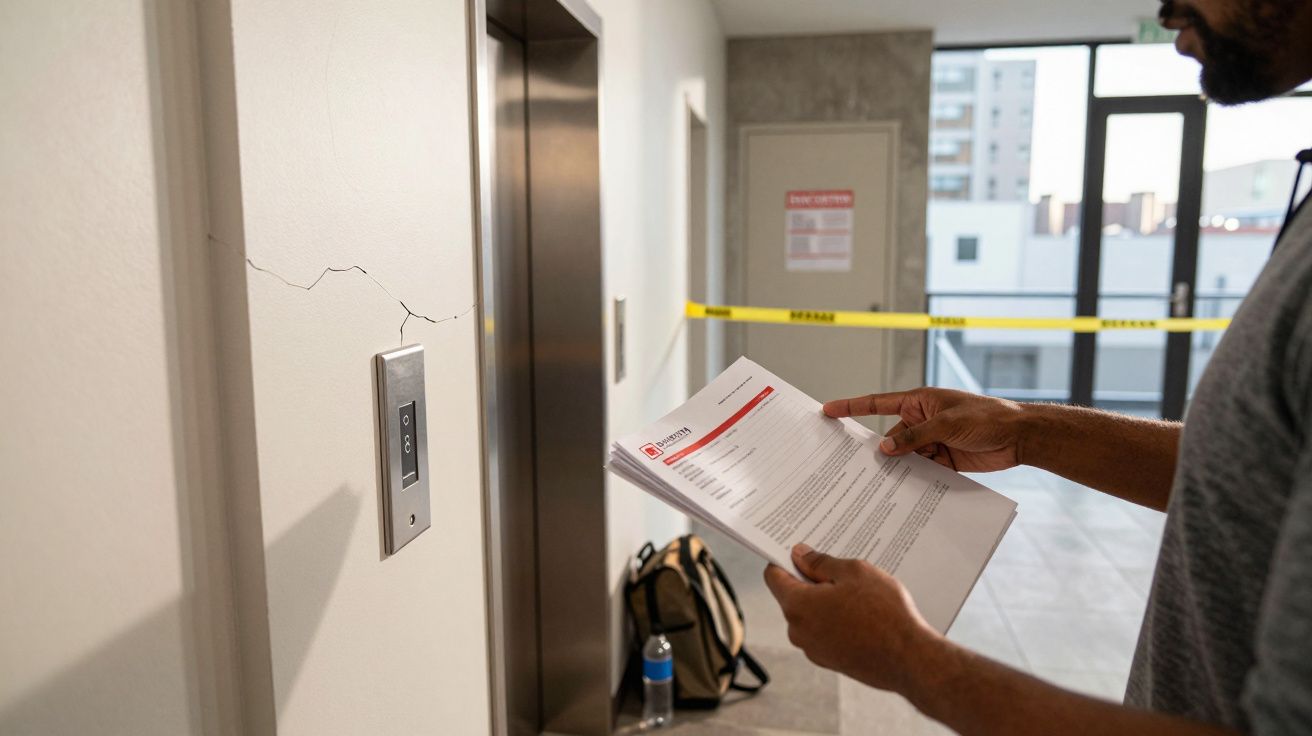

Walk into certain Japanese airports or stations and you may spot a second roll: not for you-for your phone. The logic is sneaky-simple. Your hands touch everything, your phone touches your face, and bathrooms are where people finally pause long enough to do something about it.

It’s toilet paper that never actually meets a toilet. In a country where public etiquette is an art form, this tiny design tweak lowers a thousand micro-anxieties. You leave cleaner, your phone leaves calmer, and the space does what it should-soothe, not stress.

This trend didn’t come out of nowhere. A few years back, an airport activation by a telecom brand tested “smartphone toilet paper,” a quirky campaign that suddenly felt useful. Photos went viral, travelers chuckled, and then the idea quietly stuck. Now you see variants in malls, stations, and highway service areas.

At the same time, Japan’s bidet culture kept rising, with roughly eight in ten households owning a washlet. Less paper for the body means space on the wall for something else. The bathroom turned into a tiny hygiene station for the object people touch over 2,000 times a day.

It’s not only cute or clever. It’s practical design born from a culture that notices the invisible. Phones carry bacteria and daily grime, and bathrooms are one of the few places where a “reset” feels socially acceptable. In Japan, that reset has a script: wash, dry, wipe the phone, breathe.

Culturally, it works because it avoids preaching. No one’s scolding you into better habits; they’re just placing a tool where your hands already pause. The paper becomes a gentle nudge, like the “Otohime” sound devices that mask bathroom noises-a small kindness wrapped in technology.

Try the Japanese way at home

You can recreate that calm, precise rhythm without remodeling. Add a bidet attachment to your toilet-twenty minutes with a wrench and a towel. Place a small stack of dedicated phone wipes by the sink, or keep a roll of soft, lint-free tissue in a small wall-mounted holder away from splash zones.

Pick coreless toilet paper rolls for the main job; they last longer and eliminate cardboard tube waste. Keep a small lidded trash can beside the toilet for anything non-flushable. End the routine the Japanese way: a quick, respectful fold of the paper tail for the next person. Small ceremony, big signal.

Most people miss one crucial detail: flow. Keep the phone-wipe workflow separate from toilet paper. Crossovers create clogs and side-eye. Fold, don’t crumple; use two or three squares, not a jersey-sized shroud. Let the bowl rest a few seconds between flushes.

We’ve all had that moment when the last squares are gone and the panic rises like steam. Build a backup: one visible roll, one hidden roll. Label the non-flush bin clearly. Let’s be honest: hardly anyone does that every day. You will, once you have a place for everything.

As one Tokyo restroom designer told me, the trick isn’t gadgets. It’s choreography.

“A calm bathroom is a chain of tiny decisions that remove friction. The paper just happens to be the easiest one to fix.”

- Place a phone-wipe dispenser at eye level, not knee height.

- Choose soft, fast-dissolving tissue for the toilet; sturdier tissue for phones.

- Use coreless jumbo rolls in shared spaces to cut panic runs and cardboard waste.

- Make a final gesture-fold the tail, wipe the phone, wash your hands-to close the loop.

Where this quiet revolution goes next

The world will keep talking about Japan’s bidets. The real shift might be smaller and stranger: what if toilet paper became a toolkit, not a single-use script? In Japan, the roll now signals readiness, supports hygiene, and reduces waste through coreless formats and longer-lasting rolls.

Public bathrooms are acting like design classrooms, teaching with objects instead of signs. A second roll for phones says, “Your screen matters.” A longer roll with no tube says, “Less cardboard.” A folded tail says, “Someone cared; you can too.” None of it is loud. All of it sticks in your memory.

Imagine airports with smart dispensers that track refill needs, or office restrooms that stock “disaster rolls” printed with blackout tips. Japan has already done both in pockets. The lesson isn’t to copy every detail. It’s to study how small, thoughtful moves change behavior without a lecture.

| Key point | Detail | Why it matters to the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Phone-dedicated paper | Small roll or wipes placed beside the main tissue | Cleaner screens, a calmer routine, fewer germs on your face |

| Coreless long rolls | No cardboard tube, higher capacity, fewer refills | Less waste, fewer “out of paper” panic moments |

| Behavioral signaling | Triangle fold, tidy dispensers, clear separation of uses | Shared courtesy that makes busy bathrooms feel gentler |

FAQ

- Is “smartphone toilet paper” flushable? Most versions are meant for wiping phones and going in the trash, not the bowl. Keep a small covered bin nearby.

- Why do Japanese bathrooms need less toilet paper? Bidet washlets handle cleaning with water, so people use fewer sheets. The remaining paper is for drying and finishing.

- What’s the deal with coreless rolls? They remove the cardboard tube and hold more paper. That means fewer refills, less waste, and a steadier supply in busy places.

- Will this work in a tiny apartment? Yes. Use a slim adhesive holder for a phone-wipe roll and a compact bin. One wall mount can change the whole flow.

- Are “disaster rolls” real? Some Japanese groups print toilet paper with emergency tips and stockpile it. Paper is light, stores well, and becomes a lifeline when the power is out.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a Comment